I’ve been thinking about the difference between a walking city and a driving city. The last city I was in was a driving city, this one is a walking one.

When I was a kid I always wanted one of those life-size (for kids, at least) Barbie Jeeps that you could drive around. There was a girl in my church who had pretty clothes and who yelled at her parents with little-to-no repercussions (shocking to me). She had a life-size Barbie Jeep and I coveted it.

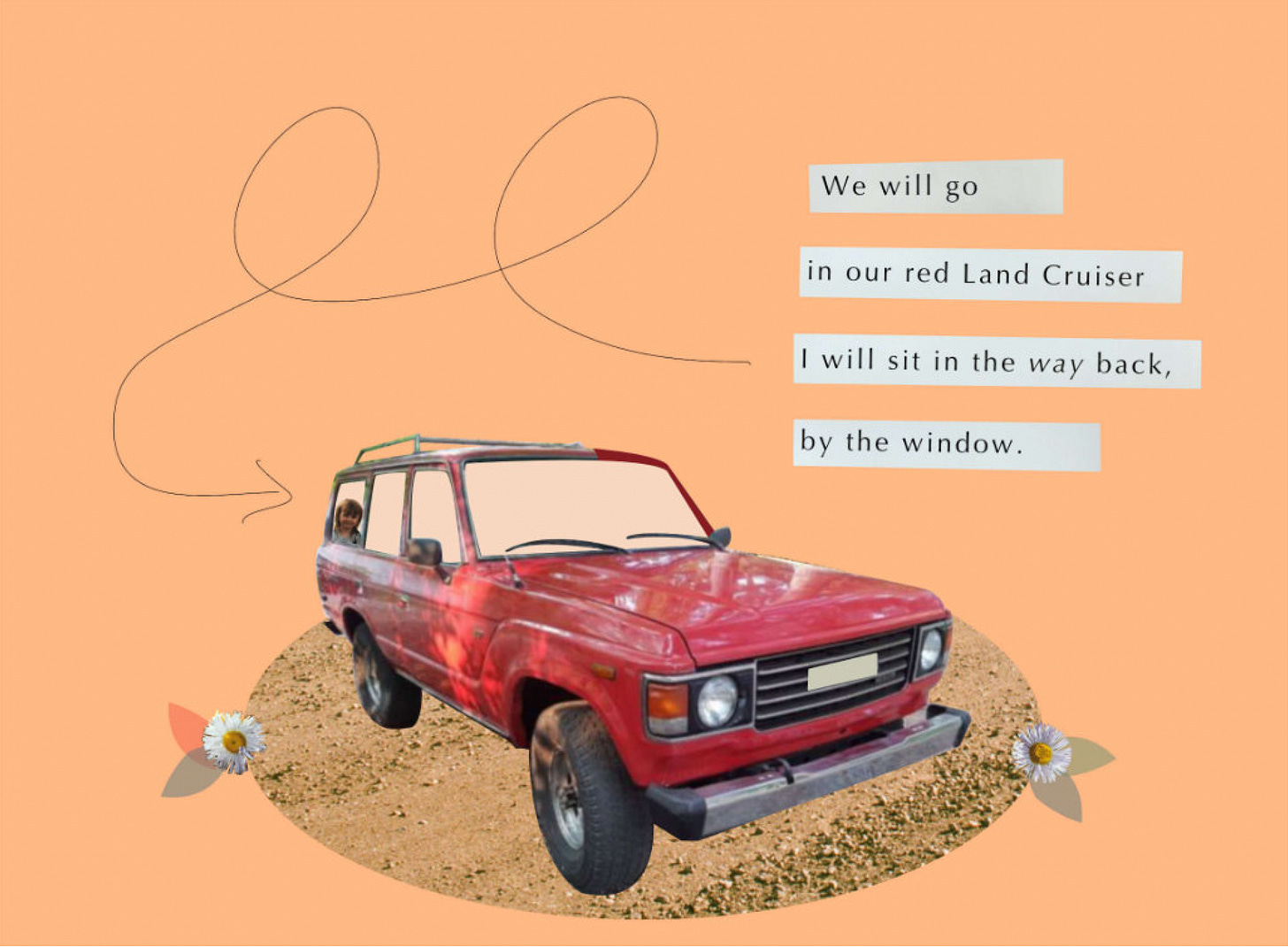

The family vehicle of my childhood was a rusted-out red Toyota Land Cruiser. There were the front seats, the back seats, and then the “way-back” which were the two additional seats my dad bolted inside the back of the vehicle. I loved the way-back and can still get in touch with the burst of a feeling I had when I would crawl over the back seat, claiming the way-back, buckling up, then bouncing around on the gravel roads that we lived on. I remember proudly telling anyone who would listen, “It’s so bouncy! It’s like riding a rollercoaster!”

My favourite times as a kid were the adventures on the other side of piling into the land cruiser; going to Horseshoe lake or exploring the northland or driving so long and so late into the night until I could see the sparkling lights of the big city where my auntie lived.

My ex-husband and I used to laugh and say that we approached road trips as if nothing could go wrong. We were lucky in that one way because nothing ever did go wrong (unless you count the time we killed that prairie chicken or when our tire blew two hours from our destination or when he yelled at me all the way to the wedding we were attending in another city). We would listen to our favourite driving albums front to back: Andy Shauf’s The Party, Oh Pep!’s Stadium Cake, Joel Plaskett’s Ashtray Rock. There is something calming about a car. I had a perfect marriage when we held hands in the front seat. I had a perfect family when we were together in the land cruiser and the big sky was wooshing by

(unless you count the hours my brother would hold his finger a millimeter away from my face while chanting, “I’m not touching you I’m not touching you I’m not touching you” or when my dad would threaten to pull the car over to spank one of my siblings or every time my mom would wait until we were all packed and then tell my dad that she wasn’t going to come so we would all beg her to “Please come, please, please come, please!”).

When I was twelve, my parents became foster parents and my two foster sisters came to live with us. We traded in our family vehicle for a sixteen passenger van with a wheelchair lift out the back. I learned to say, “They have severe cerebral palsy,” but I don’t know if that’s the right way to say that now. My foster sisters were nonverbal, but they each had their own distinct personality. K was loud, boisterous, and often crabby (but not always, sometimes she was sweet). She liked music and was happiest holding a shaker or a tambourine while listening to something upbeat in the living room. C was quiet, gentle, and a little silly. She was completely blind but had a very bright smile and liked to be in on the joke. My dad built a wooden ramp at the back of our house, we cut holes in the ceilings of our bedrooms and bathrooms and added lifts to get them out of their chairs for baths or bed. We never took a spontaneous trip to the lake or my auntie’s ever again, not with everyone, not on a whim, and I felt like an evil, awful person for resenting my new sisters for this. I knew it wasn’t their fault, but I couldn’t get rid of the evil wish that I could go back to being a kid who was sometimes happy because we were all safe in the same place on our way to an adventure. We couldn’t leave the house anymore without timing our trips around tube feedings and diaper changes and when we were out in public everyone stared at us. I was in my awkward pre-teen years and the last thing I wanted was to be stared at in the Wal-Mart aisles because I was pushing a big wheelchair. I felt evil because I knew why the locals were staring, they thought my new sisters looked strange. I felt evil because I thought so too.

We were still driving the sixteen passenger van when I was training for my license. We called it a “Hutterite van” because the only people who drove those vans in North Battleford, Saskatchewan were the local Hutterites. When we pulled into the outskirts of the Wal-Mart parking lot (it’s easier to park such a big van on the margins), we would get pointed looks from the men in suspenders and big brimmed hats.

My parents were reluctant to teach me to drive. I felt like I was always fighting to drive, but I needed to learn. I was desperate to learn. I’ve been desperate for the yelling-at-your-parents-with-no-repercussions freedom a car can bring ever since coveting that Barbie Jeep at church.

One of the days that I convinced my mom to let me drive, I backed into the beautiful wooden ramp my dad had built for my new sisters. Someone had parked the vehicle in a weird place and my mom was yelling and I decided to follow the directions she was yelling literally instead of doing what I knew to do to get out of the tight spot. I hit the ramp. I remember the yelling and the crack of the wood splitting, but I can’t remember if I drove the rest of the way in to town or not. When we came back home, the ramp was as it was before I hit it. Miraculously fixed. I went to my dad, surprised. He said, “I didn’t want you to have to think about it ever again.”

It took me two tries to get my license, but I did it.

My dad helped me find my first car: a used red 2007 Ford Escape who I named Jeffy. I got it in the final year of my English degree with the last of my student loan. It reminded me of the land cruiser my family used to drive. It was my adult version of the coveted Barbie Jeep. My favourite burned cd that I would listen to while driving in Jeffy on my way to my summer TA job at the university started with the song, “The Mother We Share” by CHVRCHES. I still feel like I’m flying every time I hear that song. I still scream-sing my same gibberish interpretation of the words in the chorus.

Jeffy was with me when I moved back home in 2014, all my things in the back teetering wildly in piles on top of each other. I would drive Jeffy into work at the Post Office each morning, trying to inhale the stretched-out sunrise over the prairie sky. I had my first panic attack in Jeffy, driving home and crying crying crying gasping gasping gasping lips tingling and numb. My first kiss with my ex-husband was in the backseat of Jeffy (he would later say it was a bad first kiss. I thought it had been a good one). One slick January morning, I was driving into work, looking at the sky, listening to Beethoven on CBC Radio while I took my usual turn slowly down the next gravel road. I lost control on the ice and spun around in slow motion while the music swelled. I remember laughing at how slow I was moving and how cinematic it felt with Beethoven’s chaotic chords playing in the background. I hit the neighbour’s mailbox and had to wait for the next farmer to come by, to pull me out.

Jeffy was my vehicle until November 2020. My ex-husband would shit talk Jeffy and I would snap at him, “Hey, he can hear you! Jeffy doesn’t owe you anything. He’s been a good vehicle.” Eventually, Jeffy became too unreliable. I had to send him to the chopper. I watched him get dragged away like a favourite dog being put down

(or how I imagine it would be to watch a favourite dog being put down. All my dogs died by strange accidents except the ones who were sick. The sick ones my dad would take into the field, feed them the best cut of meat he had, then shoot them in the head. My dad was quiet and quick enough that I never knew it had happened, but he would tell us the story of their death after and how he had cried).

After Jeffy, I drove a string of old silver vehicles that never really felt like mine. The last car I had in my marriage got hit by a drunk driver two minutes after I parked it outside my house on the last day in my home with my ex-husband, the day before I moved to my own apartment. I called my sister on the phone, yelling, “The universe is trying to flatten me,” my sister said, “No, the universe wants you to start over.” My friends lent me a car, then my sister gave me her old one. When I moved to Toronto, I gave it back.

The last vehicle I drove was the U-Haul that brought me to this walking city. I miss how far you can get with a car in a driving city. I miss how easy it was to get out of the city, to find a sky big enough to breathe in. I miss feeling like a big kid driving to my friend’s house after work for a sleepover. I miss having a tin can where I can yell at the top of my lungs.

But there is something to be said for a walking city, too. I have a few less things to yell about these days, but, mostly, it just feels really good to stretch my legs.

Talk soon,

Natahna

Hot Take/Hot Tip (formerly, “the recommends”): Listen to Annie DiRusso, especially Legs or Back In Town or Wet. <3